Dolby Atmos is a surround sound standard that provides a three-dimensional surround sound scene. Sounds not only come from the front, back and sides, as in a traditional two-dimensional system, but also from above. This adds a third dimension to the auditory soundstage. In Dolby Atmos recordings, sound engineers can adjust the "pitch" of the sound's apparent origin in the space around the viewer. A helicopter coming in for a landing, a gunshot whistling past an ear, the cataclysm of a large explosion:all effects benefit hugely from the addition of the Airborne Audio Channel.

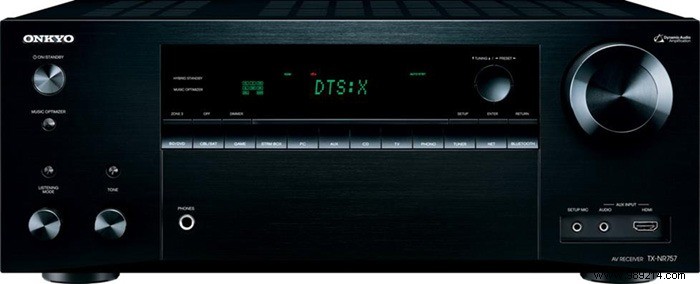

DTS:X, like Dolby Atmos, is a category of audio codecs used to save and transfer recorded audio data. The DTS:X doesn't have a specified sound system bed, which means it can run on just about any speaker mix. It uses the royalty-free Multi-Dimensional Audio (MDA) platform, while Atmos uses proprietary systems. This makes DTS:X a slightly more open system than Atmos, but generally hasn't had much of an impact on the eventual success of a standard.

If DTS:X doesn't have a reference speaker setup, what good are the engineers? First, the DTS:X receiver runs a calibration routine. This automatically detects the location and relative positions of the connected speakers. This includes ceiling-mounted speakers, a new feature in the DTS codec family. With this self-ratio, DTS:X can then translate the audio input to the corresponding audio outputs.

DTS:X translates the desired point of origin in three-dimensional space into a specific set of signals for your speakers. The codec can place sound very, very close to its intended location with almost any speaker setup. This greater flexibility makes it easier for the user to configure. It also means sound engineers can't place audio as reliably in the mix. Since there is no reference system, the placement must necessarily be less reproducible.

Cinemas make extensive use of Dolby Atmos. Cinemas have not adopted DTS:X at the same rate. This could be due to the standard entering the second-place market for three-dimensional sound. Dolby's existing business relationships also made Atmos an easy product to sell to theaters.

DTS:X can be encoded with a higher maximum bit rate than Dolby Atmos. But that doesn't make DTS:X strictly better. In audio testing, few, if any, listeners were able to reliably determine the difference between the two codecs. In reality, the difference in sound quality is probably minimal.

DTS:X could theoretically encode mathematically more accurate audio than Dolby Atmos. However, the listener would probably be unable to distinguish the difference. Dolby Atmos produces smaller files with its more efficient compressible codec, which means more data can fit on the disc. If you can't tell the difference, does compression matter? This is exactly the question the surround sound community is trying to answer.

Dolby Atmos is one step ahead of DTS:X – wider compatibility. Dolby Atmos users can get compatible audio from Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, iTunes, Vudu and most Blu-Ray releases. DTS:X, on the other hand, is only offered on specified builds. There is a certain cost to choosing the recent addition in the market.