That's not an unfair interpretation — many companies have used planned obsolescence purely as a profit mechanism — but it's not the whole story either, especially when it comes to technology. Indeed, one could argue that planned obsolescence is both necessary and inevitable in this sector, despite the waste and environmental issues that surround this low-cost and bulky model. There's a constant cycle of improving and upgrading, driven in part by the continued demand for new products, and if your phone fails in a few years, that could have been the limit of its useful life of anyway.

Planned obsolescence often means building things with lesser quality parts to ensure short lifespans and retain customers for the next model. Think of it more as a subscription model than a one-time purchase:at random intervals when your technology fails, you have to pay a fee to continue using it. Depending on your habits, this can be quite expensive. This is especially a problem when a product might still be useful, but a company is forcing it to fail somehow. A natural lifespan is one thing; intentionally breaking something is another.

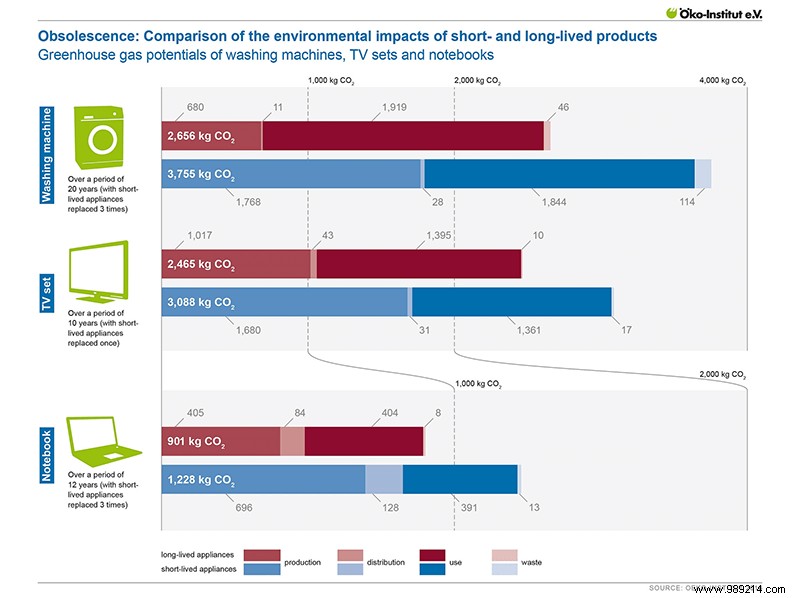

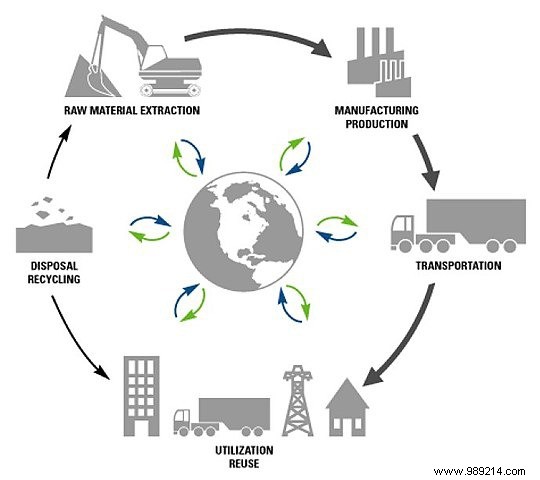

The sooner a product fails, the sooner it enters our waste management chain, which right now isn't terrible. If we are lucky, our electronic waste is recycled and reused somewhere; more likely, things end up in landfills, oceans, and incinerators, causing quite a bit of environmental damage, especially in developing countries that often face it. Planned obsolescence is accelerating the rate at which products are thrown away, exacerbating this whole problem.

Our phones seem like magic, but inside the box, they're just pieces of our planet that we've taken out and turned into things we can use. This may be bad for the environment, but it is also bad for the people extracting these resources. Many components of our modern technology come from unstable developing countries, and the money usually goes to nasty and oppressive regimes.

Consumers are therefore forced to spend more, the planet has to deal with more waste and we support military dictatorships with every purchase. This is all true, but even if it sounds bad, there are compelling counter-arguments.

Tech prices are low, and they only seem to be falling. This is probably due, in part, to economies of scale enabled by planned obsolescence. Because there is a huge and constant demand for new technologies, they can be produced and distributed in large enough quantities that the price of buying a new cheap phone every few years is probably even lower than that of a more expensive and durable phone at less frequent intervals. Short lifespans also mean manufacturers don't have to invest extra time and materials in producing durable products, driving down prices even further.

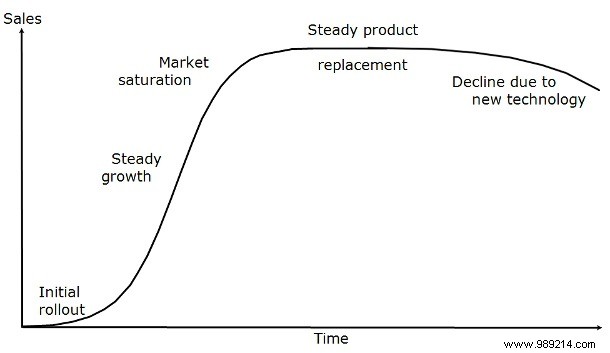

Sure, there's not much of a difference between gen six and gen eight when it comes to most of our technologies, but there's a pretty big gap between, say, four and ten. Incremental changes in processing power, features, and software add up, and these small steps are possible because there is a market for them. Someone is at the end of their tech lifespan and looking for the next best thing, which can actually be a big upgrade if they've had their last product for a few years. Short product cycles essentially translate to faster technological advancements.

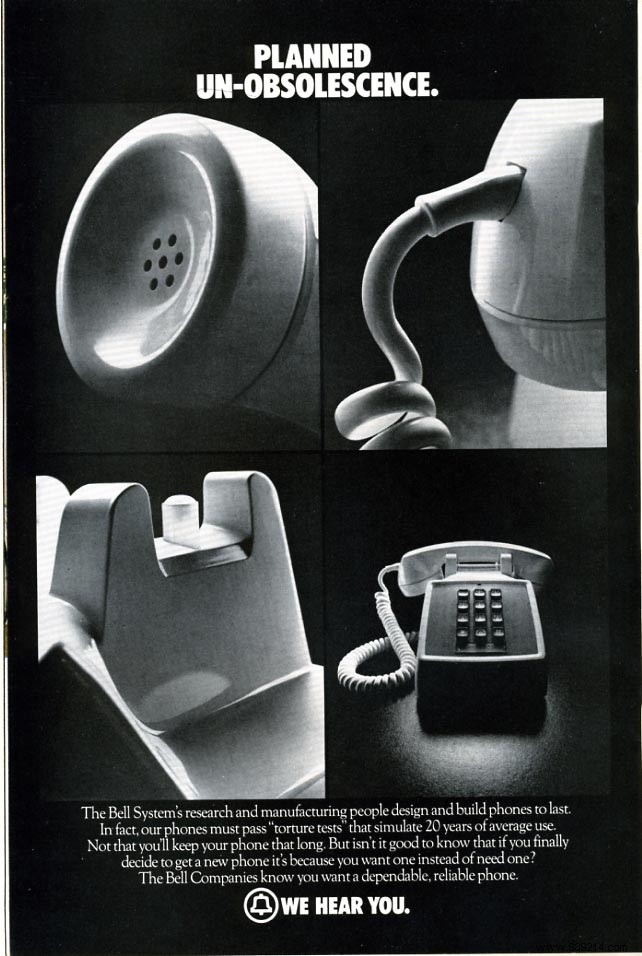

At the current rate of technological advancement, you don't want to be using the same machine for ten years (even the Bell ad above promoting ultra-durable phones agrees). It will be pitifully underpowered, things won't work on it, and it might no longer receive security updates. It's not because the money-hungry corporations designed your machine to fail; it's because technology in general has improved while yours has stayed the same. It just doesn't make sense to create more expensive, capital-intensive technology when it will be irrelevant in about the same amount of time anyway. We may be using fewer resources.

They don't make them like before, but they probably don't make them like they will in the future either. Even though our system seems to depend on a constant stream of innovation and upgrades, it leads to a lot of waste, and there could arguably be a better way.

One idea that is slowly gaining traction is modularity:what if we could buy a phone with upgradable hardware? Several, like the FairTelephone and Moto Z, allow you to swap out components if you want extra power or functionality. The FairPhone, in particular, allows you to replace just about anything you want, from the battery to the circuit boards. They also source materials in the most ethical way possible and encourage recycling.

It's not a one-size-fits-all solution, but a relentless process of innovation and upgrading seems to be the way the future will unfold, and short and disposable product cycles, although arguably not as bad as they say. , are not a very durable route.

Image credits:Comparison of environmental impacts of short and long life products, Product lifecycle, Fun with graphics, Non-planned obsolescence